Japanese Heels – A scent of ice

- Details

- Written by M.me Red

Thoughts, words, visions, fragile as the thinnest of heels. A column by M.me Red.

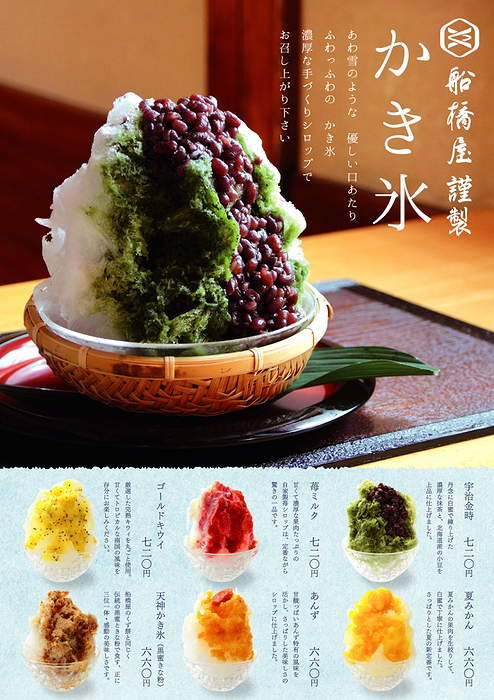

Once more a sunny summer knocks at the door of m.me Red, and she finds herself thinking of the best way to cool oneself, at least according to the Japanese: kakigōri かき氷, shaven ice with syrups.

In the hottest months one can find, along Japan's streets, the traditional red and blue banners signaling the stalls where once can find refuge from the extreme heat of the nation's summers.

Kakigōri is the king of street food in summertime and a fixture of matsuri from June to September, but it also found a home in the pages of many novels and stories, perfect fit for a summer reading.

It was great. That crunchy, sugary ice on the tongue felt like frozen cotton. It would melt in an instant and would go down, in every corner of the body, as if a breeze was blowing inside me ( Ogawa Ito, Farewell Supper, Neri Pozza 2012).

While reading this, we feel as if we could taste the sweet freshness of shaved ice together with little Mayu, the tender protagonist of the short story 'Grandma's Shaved Ice'. The story revolves around the old grandma's desire for kakigōri. But not any one: a perfect mound of ice, resembling Mount Fuji.

Apparently, in order to make his signature shaved ice, the owner of the shop used only mineral water. In winter he collected water in a sort of pool, he waited for it to freeze over, he cut it in shapes and kept it in cellars. I don't know how ice made this way could differ from normal ice, but I remember my father talking of it fondly, saying it had an exceptional taste. 'With this ice' he said, 'one could make an excellent whiskey on the rocks' (Ogawa Ito, Farewell Supper, Neri Pozza 2012).

Food for the body and food for the soul, containing a world of memories and feelings that has to power to re-establish bonds and heal the soul.

It seems this power was already known in the Heian period, in which the ice was preserved underground, to be scraped and sweetened with grape syrup for the enjoyment of rich, noble families. A refined pleasure that Sei Shonagon, the most snobbish dame of which we have records, would have surely appreciated:

42.

Precious details.

Wearing a red dress and comfortable, white gown. Duck eggs. A sweet of grape sugar, kept in ice and presented in a metal cup. A crystal rosary. Budding flowers. Plum flowers when snow falls on them. A beautiful child eating strawberries. (Sei Shonagon, The Pillow Book, SE).

The dessert's popularity came much later: only in the Meiji era kakigōri took its present appearance, and became a popular phenomenon in the '20s. Up to that time ice was a precious commodity, at least until entrepreneur Nakagawa Kahe began importing ice from Hokkaido to Yokohama and opened the first kakigōri business in 1972 in Kanagawa.

Thanks to the invention – just a few years later – of the first ice machine and, at the beginning of Shōwa era, of mechanic ice shavers, the traditional ice scoops with various toppings such as tapioca balls, milk, azuki, matcha and so on became a symbol of hot Japanese summers.

At the tables by the stall everyone was happily eating away at their shaved ice, eyes fixed on the ice scoops. […] 'Wait a bit' the shaved ice man told me after a while, when I thought he was just not going to listen. He started cranking the lever of his machine and, in a few instant, the big glass was full of pure white ice. [...]The man took the syrup bottle and carefully poured some on the ice. Then he told me to hand him the ice box, where he carefully stored the shaved ice. (Ogawa Ito, Farewell Supper, Neri Pozza 2012).