Attack on Tokyo subway – Twenty years later.

- Details

- Written by Artemis

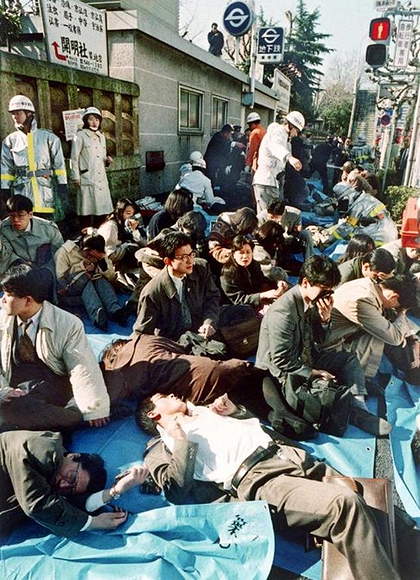

It happened on March 20, 1995. On an early spring morning, a few adepts of Shoko Asahara's sect, the Aum Shinrikyō, took a few of Tokyo's busiest subways and dropped a few concealed bags, lancing them with the tip of their umbrellas.

Not all bags broke, a 'fortunate' incident that probably contributed to keeping the number of deaths at thirteen. Those bags were filled with liquid sarin, a nerve gas one drop of which is enough to kill a grown man.

That's how Kazumasa Takahashi, a worker for the Tokyo subway, died: trying to mop up a puddle of sarin. His swift intervention – although he didn't know what the liquid actually was – saved lives, but he was not the only one who sacrificed himself. Some moved the bags to their offices and died there, sparing others in the process.

Still, in spite of these acts of heroism, thirteen died and more than six thousands were poisoned. Some still today have to deal with the aftereffects of sarin poisoning.

Today the mastermind of the attack, Shoko Asahara, elderly and blind, is on death row along with most of its accomplices. Who are these terrorists? Most of them are doctors, scientists, people of great culture who trained in Tokyo's best universities. Kimiaki Nishida, professor of psychology at Rissho University, points out a disquieting parallelism: “Similar personalities are nowadays recuited by IS. They are youngsters looking for a place where they might feel useful and wanted”. And this is why he stands against the death sentences: “The cult members had no ill feelings toward the victims, they simply obeyed orders from a master they thought infallible. What was really on their minds and in their hearts?” In these difficult days it seems Japan might miss out on a chance to understand what really hides in the mind of a religious terrorist.

Just as mysterious are the reasons why the order was given. Shoko Asahara was obsesses by persecution manias, or maybe he wanted to hide something or give a warning. His attempts at official politics were a failure, although the Aum Shinrikyō had grown to over 10.000 adepts since its foundation in 1980.

Today the Aleph – Aum's heir – has barely 1.650 adepts, and it's crushed by debt following reparations to the victims, who still don't fell safe enough and ask for more protection, fearing new attacks. Kenji Utsunomiya, the victim's defendant, points out that the sect is still recruiting: “More and more young people feel alienated in contemporary society, and could join these groups to gain acceptance.”

Further, there is disappointment for institutional failure in what was perceived as one of the safest countries in the world. Utsunomiya adds: “No health checks have ever been done on the victims.” “Lawyers should have done more, and so the police and doctors”, adds Nakano, another of the victims' layers.

Still, twenty years later, there is no closure in spite of attempts to move on and forget.

SOURCES:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3002043/Tokyo-subway-attacks-Japan-baffled-20-years-on.html

http://www.dpa-international.com/news/asia/victims-of-tokyo-sarin-attack-struggling-20-years-later-a-44633377.html