Japanese Heels- The Land of The Rising Sun's Lost Youth: “ The Generation of the Sun”

- Details

- Written by M.me Red

Thoughts, words, visions as frail as the thinnest heels. A column by M.me Red.

Mishima Yukio told me that Japanese literature is full of mental cruelty; I wanted to show active physical cruelty instead. (Ishihara Shintaro).

Marking the literary debut of Ishihara Shintaro (1932-), today a well known and controversial political figure, is the award of 1956's prestigious Akutagawa prize to his debut novel, Season of the Sun (Tayou no Kisetsu).

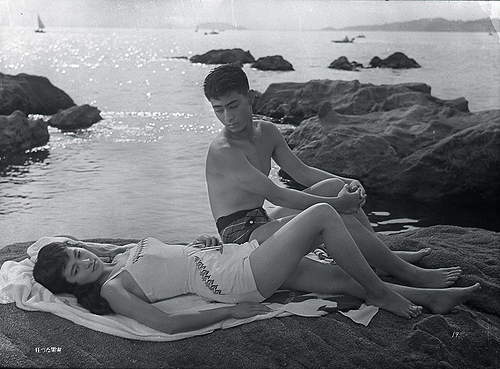

The success of this and other of Ishihara's novels is closely tied to their movie transpositions and to the career of his brother, Ishihara Yujiro (1934-1987). Both offer a portrayal of the postwar generation in Japan, depicting the rise of so-called 'mass culture'. In fact, Yujiro himself becomes the face of what comes to be called tayozoku, 'the Generation of the Sun', the scandalous youth portrayed on the pages of Season of the Sun, Crazy Fruit (Kurutta Kajitsu, 1956), The Perfect Game (Kanzen na Yuji, 1956): young kids from affluent households, obsessively seeking their next thrill, the next rule to break. Against a backdrop of luxury villas and resorts, tangible signs of social status, rolls a slideshow of violence, alcohol, psychedelic trips and extreme sex.

A love triangle is the center of Kurutta Kajitsu: bored by summer vacation, two brothers end up having a flirt with the same woman. In a crescendo of violence and depravity, Haruji, the younger and troublesome brother, discovers the betrayal and does not hesitate to kill the two lovers in a tragic ending, cutting short lives already eaten up by existential void and a spasmodic search for immediate pleasure.

It's the years of the mohaya sengo de wa nai ('no more postwar'), the years of the economic miracle and the desire to leave the conflict, the loss and the difficult years of American occupation behind. In this context Ishihara's novels and their film adaptations exemplify the aspirations of a middle class seduced by the American dream (expensive houses, yatches, foreign cars); but also feel the anxieties of a traditionalist society toward the Fifties' global youth cultures. Provocative and scandalous, they make fun of backward ways of life made redundant by new lifestyles, values and morals torn to pieces by the bombings of WWII.

This cynicism that takes apart Japan's traditional ethics is part of a larger phenomenon, a progressive 'Americanization' of Japanese culture. In literature, this translates into a fast paced language that privileges present tenses and hybridization, slang and English terms. That same language that can be found, against a jazz backtrack, in films, on magazines, in ads and the early photo romances that appear from the '50s onward: the 'Shintaro Boom' kickstarts that collaboration between visual and textual that, from around 1956, will become the language of youth subcultures, developing in the following decades along with new media.

Of course this new ways of live come under heavy scrutiny by the establishment, and Inshihara's novels are frequently accused of having a negative influence on the younger generations, though their importance is hard to deny. The awarding of the Akutagawa Prize to Season of the Sun marked a watershed in postwar Japan's culture: it re-ignited the debate on the value of so-called mass literature against high literature; a debate that will keep going until the '80s, when authors like Murakami Ryu and Tanaka Yasuo will bring to the fore the 'crystal tribe', which will take the place of the 'generation of the sun'. Born in the same years in which Ishihara was met with success, these new writers continue the tradition of narrating the disillusion of a generation steeped in consumerism, moral lacks, luxury, drugs, violence, sex.

(from Roberta Novielli- Paola Scrolavezza, Lo schermo scritto. Letteratura e cinema in Giappone, Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina, Venezia 2012)

HERE IS THE TRAILER: